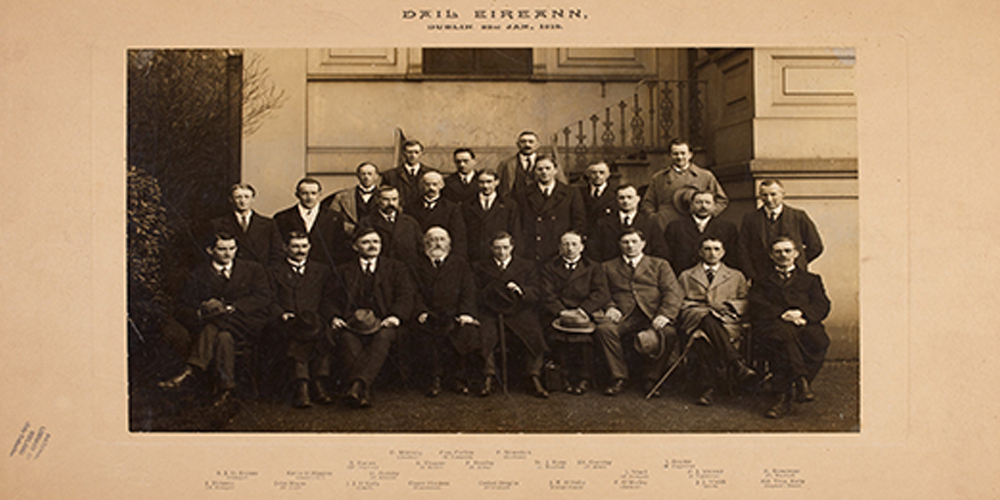

1919

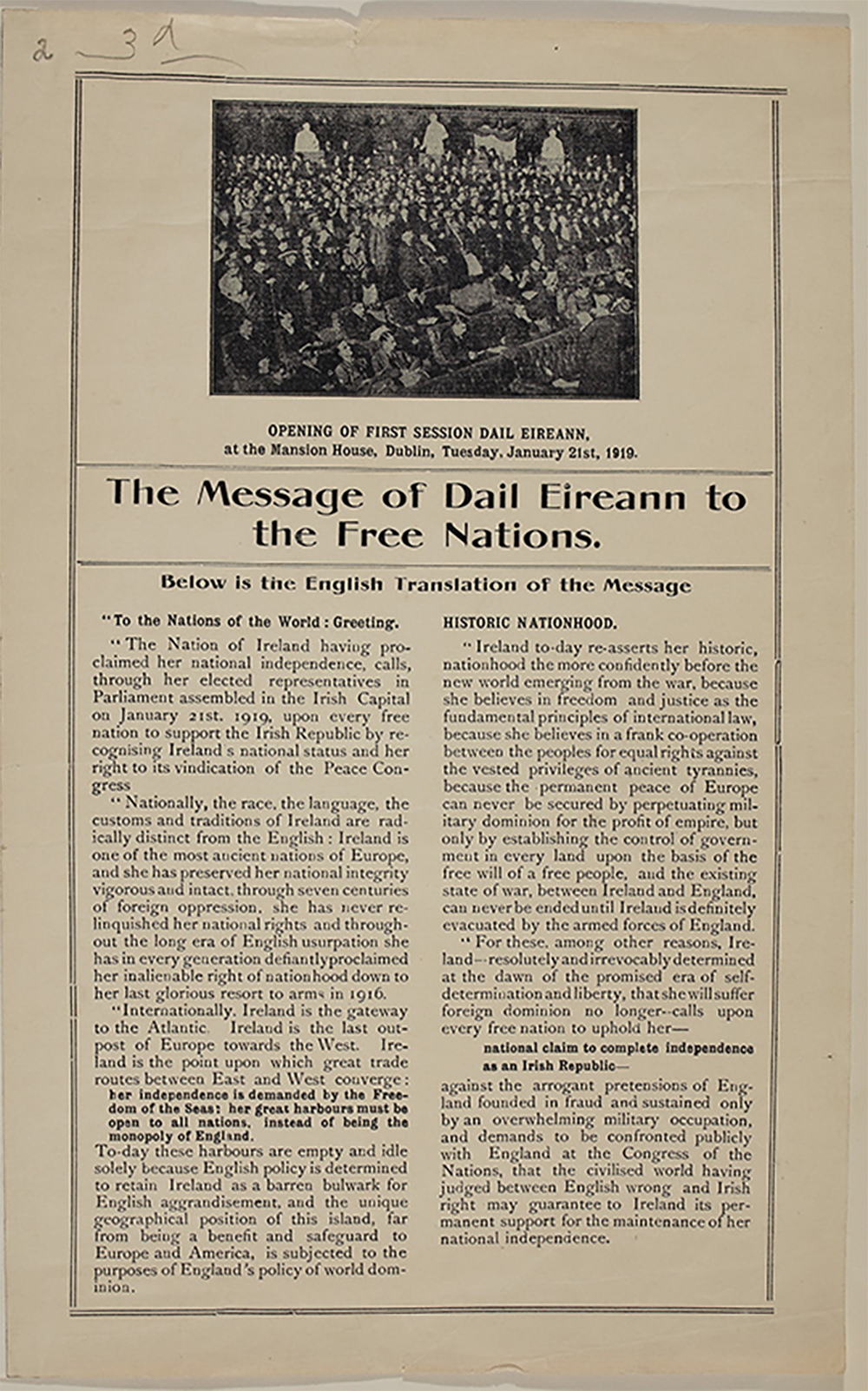

Our first steps on the world stage were taken on the floor of the Mansion House in Dublin. At its first sitting on 21 January 1919, Dáil Éireann adopted not just the Declaration of Independence, but also a Message to the Free Nations of the World

In it, the Dáil pledged to 'resume that intercourse with other peoples which befits us as a separate nation.’

The following day, Count George Plunkett was appointed our first Minister for Foreign Affairs.

Three days earlier, a peace conference had begun its work in Paris, its task a remaking of the European map after WWI.

The future president, Seán T. Ó Ceallaigh, was sent to Paris in early February as Ireland’s first envoy abroad, to gain a hearing at this peace conference.

And in April the Dáil voted enthusiastically to seek membership in the League of Nations, the first organ of global governance that the conference would bring to life.

Over the next three years, envoys were sent to the capitals of Europe, across the United States, to South America and beyond. Cooperation flourished with Indians, Egyptians and others who sought their independence. A treaty was even negotiated with the Bolsheviks in Russia.

A foreign ministry operating from a secret Dublin address was created to support this work. Like other clandestine Dáil offices, it would disappear through a skylight or down a drainpipe when Crown forces came calling.

No country had recognised the Irish Republic by the time negotiations began for what would become the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921.

But it is from the ideas and aspirations of this period that the beginnings of Ireland’s foreign policy can be traced.

And it is from the Dáil diplomatic service that the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade of today would grow.

What were these ideas?

A stirring appeal for recognition, the Message was also an embryonic diplomatic manifesto.

It set out a first geopolitical vision of Ireland:

‘Internationally, Ireland is the gateway of the Atlantic. Ireland is the last outpost of Europe towards the West: Ireland is the point upon which great trade routes between East and West converge: her independence is demanded by the Freedom of the Seas: her great harbours must be open to all nations…’

It reads as a document of its time, yet there is a modern ring to some of its language.

It affirms ‘freedom and justice as the fundamental principles of international law;’ speaks of ‘a frank co-operation between the peoples for equal rights;’ and upholds the principles of self-determination as the only basis for a lasting peace ‘by establishing the control of government in every land upon the basis of the free will of a free people.’

We might recognise this today as a values-based foreign policy.

We would also recognise a belief in multilateral solutions, the rule of law, and the rights of all countries to make an international contribution regardless of size.

There was an attempt to reach out to the Irish diaspora – plans were even hatched for a global Irish race conference and secretariat.

Consular assistance was provided to the families of republican prisoners in British gaols.

And despite hardship at home, the Dáil voted funds for famine relief in Russia.

Some of these themes would have greater or lesser significance in the decades that followed, and our foreign policy would constantly evolve to meet changing needs and circumstances.

But we can discern some of the contours of our foreign policy today from these first steps on the world stage a century ago.

Ambassador Gerard Keown

About the Author

Gerard Keown is currently serving as ambassador in Warsaw.He is the author of First Among the Small Nations, and previously was head of the Strategy & Performance Unit in the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade,where among other projects he oversaw the development of an exhibition on the history of the Department.