Seamus Heaney's worldwide impact celebrated during major international poetry conference in Belfast.

By Peter Kissel

April 29, 2014

On April 10-13, 2014, Queen’s University’s Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry in Belfast hosted “Seamus Heaney: A Conference and Commemoration” in honor of the poet’s 75th birthday. Ciaran Carson, Director of the Centre, opened the conference with a passage from Heaney’s The Blackbird of Glanmore:

On the grass when I arrive,

Filling the stillness with life,

But ready to scare off

At the very first wrong move,

In the ivy when I leave,

It’s you, blackbird, I love.

The theme of the blackbird, symbol of the Seamus Heaney Centre for Poetry, guided the conference through four stimulating days of lectures, poetry, panel discussions, and music in celebration of the great poet’s life and legacy. Seamus Heaney, the Nobel Laureate who died unexpectedly on August 30 of last year at the age of seventy-four, is revered as a universal and unifying figure, perhaps the only one, in Ireland. But his renown extends throughout the world. Indeed, in a poignant reflection of his international impact, before his untimely death Heaney had been scheduled to read at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington during the same week as the conference at Queens.

In the opening plenary lecture, author, poet and critic Neil Corcoran noted the universal appeal of Heaney’s poetry by reminding the audience that “Heaney never became a statue of himself.” Corcoran demonstrated Heaney’s power by reviewing The Strand of Lough Beg, a deeply personal homage to a cousin who was murdered during sectarian violence, as well as Sweeney Astray and several other works. Heaney remained grounded in the farm community and simple life in which he was raised, yet was able to speak to a constantly evolving world. The poet Paul Muldoon elsewhere observed that Heaney started life in a peasant, almost medieval, world that hadn’t changed in five hundred years, but his last message was, fittingly, a text message, in Latin, to his wife Marie: Noli timere, “Do not be afraid.”

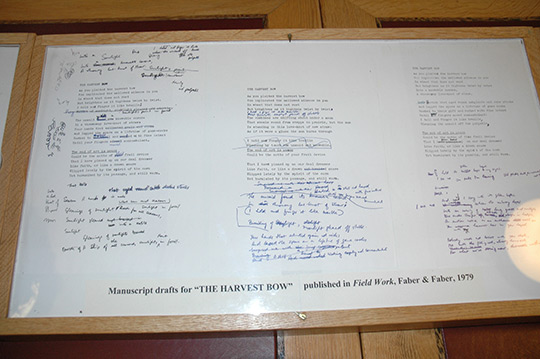

A lecture by critic Peter McDonald, Professor of Poetry and English at Christ Church, Oxford, was compelling for its focus. McDonald spent over an hour deconstructing one poem with such insight and enthusiasm that I left the lecture convinced that The Harvest Bow, which I had never read, was the greatest poem Heaney ever wrote. Among other Heaney poems of impact analyzed during the four-day conference were Digging, The Tollund Man, Death of a Naturalist, Follower, Mid-Term Break, Station Island, and Postscript.

In another keynote address, Jahan Ramazani, Professor of English at the University of Virginia, addressed what he called “Seamus Heaney’s Globe,” i.e., his “totality of the world,” encompassing the dislocations of cross-cultural and lingual travel, and alphabetical journeys through poetry. Another speaker, John Wilson Foster, Emeritus Professor and Honorary Research Fellow at Queens, kept Heaney very much alive by explaining that criticism properly continues after a poet’s death and should be viewed as kind of an ongoing dialogue with the writer.

The various panelists, consisting of scholars from around Heaney’s globe, from the U.S. to China, were lively and enlightening. “Heaney and America” focused on the poet’s time at Berkeley and the influence that experience had on his poetry. “Politics and Poetics of Reconciliation” addressed the subtle messages in Heaney’s poems that touch on the anguish of his country. A presentation by Barbara Gerner de Garcia, Professor in the Education Department at Gallaudet University in Washington, DC, on “Heaney in Translation: The Written Word Transformed By Sign Language,” featured a video of two deaf students interpreting Postscript into American Sign Language, followed by de Garcia’s own interpretation back into English of her student’s interpretation.

The conference also featured nightly readings by notable Irish and British poets. Carol Ann Duffy, Britain’s Poet Laureate, opened the readings with The Blackbird of Glanmore in Belfast’s historic Ulster Hall (a grand setting but not ideal for poetry readings due to its unfavorable acoustics). Other featured poets on the opening night included Chair of Irish Poetry Paula Meehan and Scottish poet Don Paterson, winner of the Whitbread Prize, the Forward Prize for Best First Collection, and the T.S. Eliot Prize.

The conference dinner on Friday evening in Belfast City Hall was preceded by readings and music by Ciaran and Deirdre Carson, poetry by Belfast’s first Poet Laureate Sinead Morrissey, and beautiful ballads sung by traditional Irish songstress Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin, who was accompanied by the evocative playing of Zoe Conway on fiddle and Macdara Graham and John McIntyre on guitar. Van Morrison was among the guests enjoying the concert and the dinner. Saturday’s events included more readings by Paul Muldoon, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and the T.S. Eliot Prize, as well as by acclaimed poets Leontia Flynn, a winner of the Forward Prize for Best First Collection, Nick Laird, and David Wheatley.

On Sunday afternoon, a tour into the Derry countryside visited Heaney’s home townland of Bellaghy. The Bellaghy Bawn Centre for Poetry and History is housed in an old English plantation that has been occupied at various times since 1614 by English planters, a vintner, native Irish settlers, families, and as an English army barracks. Today it houses a library containing original manuscripts of some of Heaney’s most notable works, vividly demonstrating the poet’s extensive handwritten edits to his poems, and by extension, the tremendous effort that goes into writing great poetry.

On the grounds of the Bellaghy Bawn Centre is a compelling sculpture of a turf digger, that was dedicated by Heaney in 2009.

The sculpture was inspired by Heaney’s iconic poem, Digging:

Under my window, a clean rasping sound,

When the spade sinks into gravelly ground:

My father, digging...

...

Between my finger and my thumb,

The squat pen rests.

I’ll dig with it.

Heaney’s grave at nearby St. Mary’s Church sits in a peaceful corner of the cemetery. The plot is next to memorials to his parents and his brother Christopher, who was killed in a road accident at age three, inspiring Mid-Term Break.

The closing session, led by Dr. Eamonn Hughes, Assistant Director of Queen’s Institute of Irish Studies, was inspiring and fun, with just the right dash of emotional tributes. Northern Ireland poets Gerald Dawe and Maeve McGuckian offered moving personal reflections and poems about the impact Heaney has had on their writing careers. Heaney’s close friend and fellow poet Michael Longley concluded the conference by sharing tales of his competitive friendship with Heaney and his recollections of his own father. Longley, a contemporary of Heaney’s, closed with a new ode he has written to his friend Seamus, and brought the house down by spontaneously noting that “I’m glad to still be here” while dancing a little jig before exiting the stage to thunderous applause. It was a brilliant final act to a most memorable conference.