Lecture by Ambassador Mulhall at the West Cork History Festival

Speech

10 August 2019'America 1776, Ireland 1919: Declaring Independence', a lecture by Ambassador Mulhall delivered at the West Cork History Festival, 10 August 2019

Introduction:

About a year ago, I was invited to deliver a lecture at the University of Virginia as part of its Ambassadors' Series. The University kindly allowed me to choose my own topic for a talk that took place in April of this year.

It did not take long for two thoughts to form in my mind. I knew that I would be speaking at the University founded by Thomas Jefferson and in the Rotunda Room that Jefferson himself designed. And my talk would take place in the centenary year of Ireland's own Declaration of Independence issued by the First Irish Dáil (Parliament) in January 1919. So, in that place in Virginia so closely associated with the author of the American Declaration of Independence, I set out to look at the two declarations and their contexts to see what could be gleaned from comparing them.

The American Declaration of Independence in July 1776 was an epoch-making moment in global history, one that played a vital role in ushering in the modern era in which we still live.

The words Jefferson wrote in the Declaration's opening paragraphs - "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." - are among the best-known political statements in world history.

America's Declaration of Independence did not always enjoy such canonical status. It took years for its significance to be appreciated and for the text to become the object of veneration it is today.

Ireland's Declaration of Independence in January 1919 is far less well-known. In Irish history, it has been overshadowed by the Proclamation of the Irish Republic issued on Easter Monday 1916 on the first day of Ireland's Easter Rising. Our 1919 declaration has attracted scant attention from Irish historians. There is no lore surrounding it and we have little knowledge of when, how or by whom it was written. It is a forgotten Declaration. There are books on the history of that period in Ireland that do not even mention the Declaration. It was issued on the day of the Soloheadbeg ambush which is generally seen as marking the start of our war of independence, a 30-month struggle that has attracted huge attention from historians to the detriment of the more prosaic events that took place in Dublin's Mansion House.

The treasured status of Ireland's 1916 Proclamation notwithstanding, there are, I think, good reasons for viewing the 1919 document as part of a transformational era in modern Irish history, and as one that bears some comparison with its 1776 American predecessor. After all, like the American Declaration, it was adopted by a group of politicians who were representative of the people. In the Irish case, those who declared independence had been elected in December 1918. Moreover, unlike the 1916 Proclamation, Ireland's Declaration of Independence, like its American predecessor, set in train a process that led to actual independence, albeit that the legacy of 1916 loomed large for those involved in that final phase of struggle for independence. We ought, I think, to be more aware of the legacy of 1919.

The Prelude to America, 1776:

The roots of the American revolution are planted deep in the soil of American history and in the very different environment in which European settlers lived since their arrival in the New World in the early 17th century.

Ironically, America's progressive alienation from Britain was spurred by an event that had highlighted the togetherness of the Mother Country and its American colonies, the French and Indian Wars (known in Europe as the Seven Years' War) when the colonies sided unreservedly with Britain in opposition to France.

Britain's victory over France gave it control over vast swathes of territory in the American mid-west, but it also left the British Exchequer deeply indebted. The response from London was to try to make its increasingly-prosperous American colonies bear a larger share of the British State's financial burden. Those efforts at extracting revenue from the Americas generated resentment, resistance and ultimately rebellion.

Friction between London and its colonies brewed gradually and at the first two Continental Congresses, delegates held on to the hope that the trans-Atlantic difficulties could be resolved and there was no headlong rush towards independence. Indeed, throughout the American War of Independence many Americans remained loyal to the crown and some 10,000 American loyalists fought with the British against the independence movement. 60-80,000 left the United States during and after the war of independence, although many subsequently returned and we reintegrated into American society.

Although it is possible to find many political, economic, and philosophical origins to what happened in America in the 1770s, my sense is that the American revolution was ultimately a product of the geographical distance between Britain and its American colonies. It is hard to imagine that London could have indefinitely held sway over such distant colonies that had such a different composition from 18th and 19th century Britain.

In the 1760s and 1770s a gradual rift occurred between the Imperial centre in London and its colonial possessions which bred misunderstanding and resentment between the two. The independence movement was also fuelled by powerful ideas drawn from the European enlightenment, although the weight to be given to these ideological influences as opposed to social and economic elements has long divided American historians.

The American Revolution succeeded because the colonies had become developed societies endowed with resources that made them capable of standing up to pressures from the metropolitan centre. The distance separating Britain from America made it difficult for Britain to impose its will on the rebellious colonies. Revolutionary America also benefited from support from France, Britain's most persistent and determined 18th century Great Power rival.

The Western Hemisphere into which the United States came in the 1770s had relatively few centres of power. Spain, Portugal, France and Britain controlled the Americas while in Europe there were five Great Powers all Empires and monarchies - Britain, France, Austria, Turkey and Russia. Germany was politically fragmented as was Italy but both possessed a degree of cultural unity centred on their respective languages. The United States was a major disrupter, a state based on principles that had little or no precedent in European history.

The American revolution's impact on Ireland:

Events in America stirred things up in Ireland. As the Irish historian Roy Foster has put it, "The radicalisation of Irish political life" was part of "one great theme from the 1770s: the impact of America." This led to the rise of a form of colonial nationalism out of which emerged an Irish Republican tradition that eventually delivered independence to Ireland during the first quarter of the 20th century. The 1798 rebellion of the United Irishmen, inspired by developments in America and France, became a foundational moment in modern Irish political history. 20th century Irish nationalism traced its roots to the United Irishmen and those who met in Dublin would at least have been conscious of the legacy of the leader of the United Irishmen, Theobald Wolfe Tone. One 1916 participant, Seán McEntee observed that without Wolfe Tone, "there might not have not have been a Rising and almost certainly not a Republic of Ireland."

The aftermath to 1798 highlights the differences between the American and the Irish experience. Whereas in America's case, distance acted as an ally of the rebellious colonists, in Ireland proximity to Britain meant that the rebellion could be swiftly and savagely suppressed. Lord Cornwallis who was vanquished by Washington at Yorktown went on to become Lord Lieutenant of Ireland where he helped put down the 1798 rising.

In the wake of 1798, the separate Irish parliament was abolished by the Act of Union of 1800. An American equivalent to this would be if a British victory in the war of independence had led to the abolition of the colonies' legislative assemblies. 19th century Irish history turned into an extended struggle between nationalists and unionists about the repeal or retention of the Act of Union. The 19th century driver of America's evolution was the country's westward expansion and the demographic transformation wrought by immigration including from Ireland.

Other Independence movements:

In the 143 years between the American and Irish declarations of independence, freedom movements had transformed Latin America as a succession of independent states divided up Spain's new world empire.

In Europe, there were relatively few 19th century independence struggles of the kind occurred in America in the 18th century and Ireland in the early 20th. Italy and Germany came into being in their modern form, in 1861 and 1870 respectively, through unification rather independence processes.

Belgium broke away from the Netherlands in 1831 driven by linguistic and religious differences. Greece became independent in 1832, Serbia, Montenegro and Romania in 1878 and Bulgaria in 1908, but the backdrop to the emergence of those independent states was the growing weakness of the Ottoman Empire, of which they had previously formed part. Interestingly, all those who broke away from the Ottoman Empire became monarchies of some description. Norway separated peacefully from Sweden in 1905. None followed America's route by forming a republic. Indeed, at the outbreak of the First World War, only three European states, France, Portugal and the Swiss Confederation, were neither empires, monarchies nor principalities.

Finland's break from Russian control in 1917 was perhaps the closest analogy to the Irish case. The independent states that emerged in the immediate aftermath of World War 1 - the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia - all owed their existence to the collapse of the German, Austria-Hungarian and Russian Empires. In no case was there a war of independence akin to the American or Irish struggles.

Ireland's freedom struggle:

The Irish struggle mirrored the American example in that Ireland separated itself from a successful Empire and ultimately established a republic, just as the 13 colonies had done 130 years earlier.

The Irish experience also differed from the American one in a number of ways.

First, as a neighbouring island, it was seen as intrinsic to Imperial security.

Second, 18th and 19th century Ireland was more deeply divided than colonial America on account of pronounced ethnic and religious differences. There was a more regionally-concentrated strand of Imperial loyalty in Ireland in the 19th and 20th centuries than in America in the 18th century. There was also an unmistakable class divide between Irish unionists and nationalists.

But there was also a more sustained resistance to British rule in 19th and early 20th century Ireland than in 18th century America.

And, finally, Ireland was economically weaker and more heavily dependent of Britain than were the 13 American colonies.

Throughout Ireland's long 19th century (beginning with the Act of Union and ending with the passage of the Irish Home Rule Bill and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914), Ireland had never come anywhere near to prising its independence from Britain, which was the world's leading power for most of that period. There were a handful of insurrections and periodic agitations against tithes in the 1830s, against the power of the Established church in the 1860s and on land issues in the 1880s. Some reforms were extracted from the British Government, but these failed to change the essential realities of British rule in Ireland. The Great Famine of the 1840s understandably left a deep legacy of resentment in nationalist Ireland.

As in the American case, it was an international conflict that paved the way for Irish independence. In America, it was the Seven Years' War, whereas in Ireland the First World War was a catalyst for political change. It caused the deferral of Home Rule, which would have given Ireland something akin to the political system that existed in pre-revolutionary America, and in Ireland before 1800.

The war divided Irish nationalists between those who saw Ireland's prospects being best served by participation in the war and those who viewed Britain's wartime difficulty as Ireland's opportunity. The latter group organised themselves as the Irish Volunteers and, with the involvement of the oath-bound Irish Republican Brotherhood, engineered the 1916 Rising. There were also divisions in 1770s America, for example at the Second Continental Congress there were those who wanted to press on towards independence and those who sought some form of reconciliation with the British monarchy.

The 1916 Proclamation is an impressive document, asserting as it does Ireland's historic right to independence in language that still reads well today. It begins resoundingly: "In the name of God and the dead generations from which she receives her old traditions of nationhood, Ireland, through us, summons her children to her flag and strikes for her freedom."

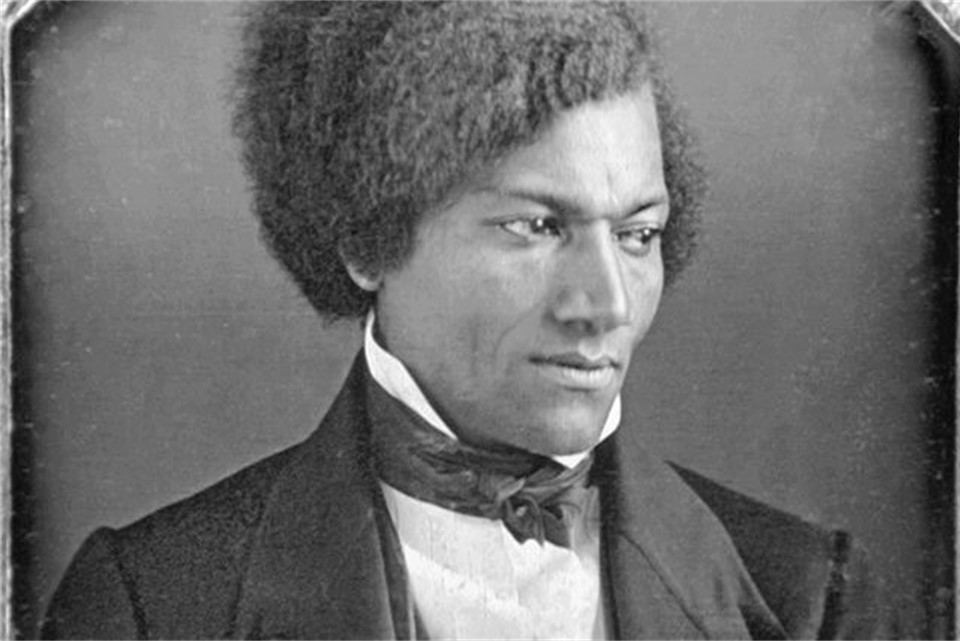

If Ireland had a Thomas Jefferson, it was probably Patrick Pearse, titular leader of the 1916 Rising and probably the principal author of the Proclamation. Pearse has been criticised for his messianic embrace of violent insurrection, but we ought to remember that plenty of blood was also spilled in pursuit of the ideals enshrined in Jefferson's Declaration.

Jefferson, who like Pearse, was not much of a warrior was also known to speak of the need for the tree of liberty to "manured" with blood. He supported the execution of Louis the 15th and hoped that the French Revolution would bring "kings, nobles and priests to the scaffolds which they have been so long deluging in blood." Jefferson also left himself open to charges of hypocrisy on account of his refusal to turn his back on slavery, which he was intelligent enough to know could not be reconciled with the lofty claims of his Declaration. Pearse’s embrace of Gaelic revivalism provided a spur to revolution in Ireland in ways not dissimilar to the impact of the enlightenment on 18th century American political thought.

The Republic declared in Dublin in 1916 was crushed within 5 days of its creation. The execution of its leaders, however, stirred nationalist sentiment and turned them into the founding fathers of Irish independence - Pearse, Clarke, Connolly, MacDonagh, Clarke, Ceannt and MacDiarmaid.

America was fortunate that the chief architects of independence, Washington, Jefferson and Adams, all survived the revolutionary war and went on to become America's first three Presidents. Indeed, there was a kind of canonical succession in the White House down to the 1820s, with Madison, Monroe and John Quincy Adams succeeding their mentors. Ireland did not enjoy such advantages in the early years of our independence, although being perceived as a founding father of the Irish Republic did work well for de Valera throughout his long political career.

In the summer of 1916, the odds were probably on the old Irish political order, the parliamentarians of the Irish Party at Westminster, reasserting itself at the war's end. But the revolutionary impulses that had been stirred did not deflate either in 18th century America or in 20th century Ireland.

The problem in both countries was similar - the insensitivity of the metropolitan power and their lack of feel for the territories they ruled. In Ireland's case, it was the attempted introduction of military conscription in 1918 that made a key difference. It united the various strands within nationalist Ireland and put the Irish Party at a deep disadvantage in the months that followed. For the leaders of the Irish Party who had supported the war effort, the First World War went on for too long. When it came to an end, they were confronted with an immediate General Election and came up against a resurgent nationalist movement, Sinn Féin, which presented itself as the heir to the sacrifices and the ideals of the leaders of the Easter Rising.

The American Declaration:

While the famous preamble to the American Declaration reads like a supreme manifesto, it is not representative of the document as a whole. Indeed, viewed in its entirety, Jefferson's text reads more like a legal than a political text. Its opening paragraph, before the famous one that established the Declaration's canonical status, says that when there is a need to dissolve established political bands, it is necessary to "declare the causes which impel them to the separation. Then in the main body of the Declaration, there is a long list of King George III's "history of repeated injuries and usurpations" which had led to "an absolute tyranny" over the colonies.

The list of grievances is long, containing 27 points, which include charges of refusing to assent to laws, dissolving representative colonial assemblies, obstructing the administration of justice, interfering with the independence of judges, keeping standing armies in place in times of peace and cutting off the colonies' trade with the rest of the world.

The Declaration concludes that George III is "unfit to be the ruler of a free people". Nevertheless, the American States had sought to secure redress from Britain which had been "deaf to the voice of justice and of consanguinity." The upshot of all of this is the assertion that "these United Colonies are, and of Right ought to be Free and Independent.

The Irish Declaration was, as we will see, a very different sort of document with a different political backdrop.

The First Dáil:

The December 1918 General Election was transformative event for Ireland. For whereas the Easter Rising had lacked a popular mandate of any kind, here was an expression of opinion decidedly in favour of Independence rather than Home Rule. The Sinn Féin party swept the boards in most parts of Ireland, completely supplanting the Irish Party that had held sway politically since the 1870s.

The elected politicians who turned up in Dublin in January 1919 (only 27 of the 73 Sinn Féin members were free to attend; most of the rest were in British custody) were in a different position to those who convened in Philadelphia in 1776.

In the American case, the transcontinental Congress was breaking new ground years considering the option of independence which would have been unthinkable in the mid-18th century, when American colonists fought alongside the British in the Seven Years' War. Most of those involved in the deliberations in Philadelphia considered themselves to be loyally British. Indeed, Jefferson wrote in 1775 that he "would rather be in dependence on Great Britain, properly limited, than on any nation upon earth, or than in no nation."

In the Irish case, the newly-elected members of parliament were part of a nationalist tradition that stretched back to the late 18th century. Indeed, in their own minds they belonged to a much older tradition of resistance to British rule. This is reflected in the opening paragraph of the Declaration they adopted.

"Whereas for 700 years the Irish people has never ceased to repudiate and has repeatedly protested in arms against foreign usurpation." English rule in Ireland was described as being "based upon force and fraud and maintained by military occupation against the declared will of the people."

In other words, there was no need to elaborate a detailed case against British rule as Jefferson and his contemporaries had thought it necessary to do. A pithy reference to centuries of English rule would suffice.

The members of the First Dáil saw the Declaration of Independence as a ratification of the Republic proclaimed in 1916. And they pledged themselves to "make this declaration effective by every means at our command." This equated to the closing lines of Jefferson's text: "And for the support of his Declaration, with firm reliance on the protection of divine Providence, we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor."

Echoing the American Declaration, its Irish counterpart insisted that only the elected representatives of the Irish people had the right to make laws binding in the Irish people. And there was another echo of Jefferson's Declaration in the demand for the evacuation of "the English garrison" from Ireland.

Although there is no soaring passage to match Jefferson's evocation of humanity's unalienable rights to "Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness", the Irish Declaration does contain an aspirational agenda: "to promote the common weal, to re-establish justice .. and to constitute a national policy based upon the people's will with equal rights and equal opportunity for every citizen."

The Irish Declaration of Independence was accompanied by two other documents which in themselves have tended to overshadow the Declaration of Independence, the 'Address to the Free Nations of the World' and the Democratic Programme. The 'Address' is clearly aimed at an American audience with its evocation of Ireland's status as "the gateway to the Atlantic". It goes on to point out that "Ireland is the last outpost of Europe to the west: Ireland is the point upon which great trade routes between East and West converge." The Address led to the dispatch of a delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference where, despite strong Irish American support, the delegates were unable to get any official hearing Ireland's claims.

The Democratic Programme was a decidedly progressive document containing such sentiments as: “we affirm that all right to private property must be subordinated to the public right and welfare.” The Democratic Programme has from time to time been cited to argue that independent Ireland had failed to live up the promise of our independence struggle. This document contains the clearest echoes of the American Declaration. “We declare that we desire our country to be ruled on accordance with the principles of Liberty, Equality and Justice for all, which alone can secure the permanence of Government in the willing adhesion of the people.”

While the composition of American Declaration of Independence is a storied event, the origins of its Irish equivalent is a bit of a mystery. It was written in a rush between the election of 1918 whose results were only announced on the 28th of December and the inaugural meeting of Dáil Éireann on the 21st of January.

According to the nationalist historian, Dorothy McArdle, who lived through this period and later wrote voluminously about it, the documents approved by the first Dáil were composed by a committee consisting of the lawyer, George Gavan Duffy (who had been a lawyer for Roger Casement at his trial for treason in 1916, was part of the Irish team at the 1921 Treaty negotiations and became, briefly, Ireland’s first Foreign Minister), the writer Piaras Béaslaí and the political activist, Seán T. O'Kelly. Of the three, O'Kelly had the most political experience, having been a prominent member of Sinn Féin since its inception in 1905. It is known that O'Kelly revised the Democratic Programme whose original draft, produced by Irish Labour leader, Thomas Johnson, was deemed to be excessively socialist.

O'Kelly was no Jefferson, but he did go on to occupy some of the most senior posts in 20th century Ireland - President, Deputy Prime Minister, and Minister for Finance during a long political career. Just like Jefferson in 1776, O'Kelly was in his 30s in 1919. The American and Irish Declarations were alike in bringing to power a younger group of political figures who constituted the founding generation in both countries.

As in 1770s America, Ireland's Declaration of Independence did not immediately create a new, independent state. In both countries, a war of independence was required to create a new political entity. The two 'wars' were, of course, very different in character. In Ireland, there were no major battles, no Bunker Hill, no Yorktown, no Saratoga. Ireland's war of independence was a smaller-scale guerrilla conflict in which the Irish Republican Army gradually sapped the will of the British Government to impose their continued rule on a rebellious Ireland.

In Ireland's case, Civil War came immediately after the advent of independence as those who insisted on creating a republic refused to accept the compromises enshrined in the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1921. This created a chasm in Irish public life that took generations to heal. Nevertheless, like the United States, an Ireland born in strife quickly became a stable democracy and 10 years after our civil war, the victors handed power over peacefully to those they had defeated militarily a decade earlier.

Conclusion:

The world of the 1770s from which the United States emerged was very different from the post-First World War era in which Ireland declared its independence. The American Declaration came at the beginning of a new era in world history which it was instrumental in creating. Irish independence came at the end of that era as war and revolution 20th century style remade the world at Versailles just as the Treaty of Paris did 136 years earlier.

The long 19th century between the American and Russian revolutions was a period during which Ireland developed a national political identity with demands for self-Government couched in various terms and pursued by different means.

In the second half of the 19th century, American became a factor in Irish politics as post-Famine Irish immigrants and their descendants were supportive of Irish movements. British concern about the capacity of Irish America to complicate UK-US relations played a part in the UK decision to concede Irish independence.

The American and Irish revolutions, separated by 140 years were similar in a number of respects. They succeeded because in both cases the British Government made important missteps and fatally underestimated their opponents. In the very different circumstances in which they operated, both sets of revolutionaries exhibited tenacity and determination which eventually saw them triumph against the odds of power politics.

Ireland’s Declaration of Independence is clearly a cousin of its American counterpart. Even the choice of its title seems to me to suggest that a conscious comparison was being sought to be made between the two. Our Declaration was also heir to a rich vein of nationalist thought from Wolfe Tone in the 1790s, Robert Emmett in 1803, the Young Irelanders of the 1840s, the Fenian Movement of the 1860s plus the many Irish parliamentarians of the 19th century who kept alive the flame of a separate Irish political identity. I do not expect Ireland's Declaration of Independence ever to acquire the iconic status enjoyed by Jefferson's master work, but it ought to be better known than it is!